Ring the ALARM! Today’s water crisis isn’t a fire drill – It’s apocalyptic

07/06/2022 / By News Editors

The following article covers the rapidly growing water crisis in the Western US. It covers how overpopulation, overconsumption, the megadrought and terrible urban planning are contributing to this catastrophe. Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink…

(Article republished from StrangeSounds.org)

The Colorado River Basin and Great Salt Lake are in trouble—both facing historically unprecedented risks. Both may be headed towards ecological disasters, years in the making, the result of a pernicious combination of aridification and poor water management, not adequately prioritizing the environment. In the Colorado River Basin and at Great Salt Lake, warming temperatures and declining river flows threaten people and nature.

Birds tell us that water-dependent habitats across the arid West are essential oases and they are in decline. The water issues created by a century of law and infrastructure development are magnified by today’s Earth changes’ crisis.

For over 100 years, we’ve operated under a legal framework in the West where water has been “developed” without consideration for the Indigenous communities that have been on the land since time immemorial, and at the expense of the environment, sometimes draining the last drops of water that supported habitats.

Across the West, water stress is evident—and people and birds will feel its effects.

Big headlines include:

With Great Salt Lake reaching its lowest ever recorded water levels, ongoing drought and increasing development pressures diverting the water flowing down rivers to the lake, a drying Great Salt Lake threatens the health of Salt Lake City residents, the future of key Utah industries, and the survival of millions of migratory shorebirds, waterfowl, and other wildlife.

We are currently in uncharted territory as we test thresholds of water levels and this could have cascading effects that would ripple throughout the ecosystem. Great Salt Lake generates enormous impact for Utah and the region with $1.56 billion annually in economic contributions through mineral, aquaculture, and ski industries, and other recreation activities.

The potential economic cost of the drying Great Salt Lake could reach $25.4 billion to $32.6 billion over 20 years, according to a 2019 report from the Great Salt Lake Advisory Council.

Much like the Salton Sea in California – another giant salt lake—which is already experiencing severe air quality issues from the exposed dry lakebed, the public health and quality of life for communities around Great Salt Lake are at risk from increased dust from larger areas of exposed lakebed. Increased dust on snow also has the potential to compound the timing of snowmelt and thus water availability.

By the way, a new interesting study has quantified the evaporation volume from 1.42 million global lakes from 1985 to 2018. Scientists have found that the long-term average lake evaporation is 1500?±?150?km3/year and it has increased at a rate of 3.12?km3/year. In other words, droughts are everywhere and loss of water is not something that will change. Sooner or later it will evaporate. (But normally some of it should reappear in rain or snow…)

Even more stunning is the realization that the Colorado River’s major reservoirs—water supply for some 40 million people—are on life support. The federal U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in March took the unprecedented step of claiming a human health and safety emergency to justify reducing the water it releases from one of those reservoirs.

At a U.S. Senate hearing in mid-June, Reclamation Commissioner Touton stated that net Colorado River water uses must be reduced in the next year by 2-4 million acre-feet, a staggering volume that amounts to about 30 percent of average consumptive use.

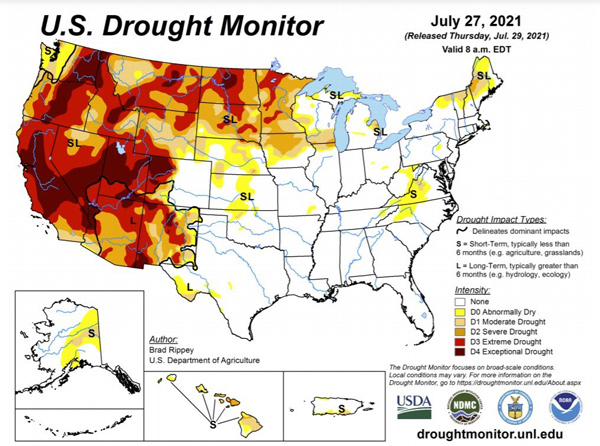

Our water supplies across the dry West are in severe crisis because of historic over-development, compounded today by a megadrought.

Warming temperatures are creating “hot droughts” that deplete flows in rivers, the flows that people and nature depend on. Today there is no longer enough water to supply all of the demands. Colorado River flows in the first two decades of the 21st century are 20 percent lower than flows in the last century.

In years when we see “average” snowpack levels in the mountains, river flows are low: last year in the Colorado River’s headwater mountains, a 91 percent snowpack yielded only a 55 percent flow.

Snowmelt isn’t reaching the rivers in the same way; warmer temperatures drive evaporation, turning the soils into thirsty sponges.

At the recent Colorado River-focused Getches-Wilkinson Center’s Colorado Law Conference aptly named “Hard Conversations About Really Complicated Issues,” Reclamation’s Jim Prairie shared the numbers behind the problem.

The volume of water flowing into the Colorado River’s largest reservoirs—Lakes Powell and Mead—has declined, while uses have not. Over the past 20 years, this imbalance has resulted in a 40 million acre-foot decline in Colorado River reservoir storage – a volume that exceeds by a factor of three the Colorado River’s annual average flow.

With so little water remaining in the reservoirs, the risks – including infrastructure failure, inability to deliver water to major population centers, and even the risk of no water flowing in the Grand Canyon – are untenable.

Moreover, while Reclamation’s call for additional water conservation in the coming year should prevent things from getting worse in 2023, it is not projected to address recovery of the reservoirs, and is not expected to solve the problem beyond 2023 unless those enormous volumes of water can be conserved year after year.

Stakes are high, and mitigation will be costly. We learned that lesson at Owens Lake in California, where the costs to remediate the lake’s historic drying after Los Angeles diverted 100 percent of its water continue to grow.

In order to address extreme dust pollution and loss of migratory bird habitat, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power invested hundreds of millions of dollars to “rebuild” the ecosystem with pumping and piping of water, infrastructure and many dust control methods – resulting in annual maintenance costs estimated at $17 million.

And the costs of restoring a small portion of flows and habitat in the once-vast Colorado River Delta underscore how much more expensive it is to try and fix rivers and lakes once they have been decimated.

This should be a wake-up call to everyone. This water crisis isn’t just impacting those of us who live in the West; it affects people who live in the East too.

Not only did the Colorado River form beloved places like the Grand Canyon, it supports an enormous part of our American economy, and has outsized importance to wildlife and birds, with around 70 percent of all species in the region depending on the riparian corridor at some point in their life-cycle. On top of that, Great Salt Lake is essential to the world’s populations of Wilson’s Phalaropes, Eared Grebe, and American Avocet.

The buzz is around shared sacrifice. Politically, all sectors need to shoulder some of the burden of reducing water use. In all likelihood, despite having senior water rights, agricultural producers who rely on irrigation with Colorado River water will be required to take compensated cuts in their water use.

As was pointed out at the Colorado River conference, we cannot conserve the 2-4 million acre-feet of water needed by evacuating the cities that rely on Colorado River water.

Water conservation in the agricultural sector has implications for rural economies and the environment. It’s a terrible situation, and important that we are doing what we can to support rural economies and to increase investments in freshwater-dependent ecosystems.

Water management systems in the West are breaking. As decision-makers revise the rules that shape water management systems, we need to urge them to incorporate today’s 21st century values, including equitable treatment of vulnerable communities that lack access to water, and emphasis on supporting water needs in the natural world around us.

With even less water, the hard conversations on water conservation efforts should include both using less water while also ensuring water supply to all households in the Colorado River region, as well as minimum water flows to protect hydrologic connections and quality habitats as crucial steps to preserving our future in this landscape.

We can’t let the water crisis allow bad projects to get approvals—they would create both short-term and long-term issues for the landscape.

We are at a fundamental inflection point for the Colorado River and for Great Salt Lake. While this is a dire update, we need to stay focused to protect our future in the West. [Audubon]

Read more at: StrangeSounds.org

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

chaos, clean water, Climate, Collapse, Colorado River Basin, disaster, Ecology, environment, Great Salt Lake, Megadrought, overconsumption, panic, rationing, shortage, tap water, water crisis, water scarcity, water supply

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 CLEAN WATER NEWS